Alamat Langkapuri in Sarandib: The World’s first Malay-language Newspaper Exiled in Ceylon

It is from the Sarandib, the Arab word for what we now know as Sri Lanka, that ‘serendipity’ got its meaning. This was coined in 1754 by English writer, Horace Walpole (1717-1797). He thought it up ‘serendipity’ after reading a Persian tale, “Three Princes of Serendip,” about good fortune obtained entirely by accident. The island of Sarandib was long known to Muslims in the nearby Malay Archipelago.

It is in Sarandib/Ceylon/Sri Lanka that Alamat Langkapuri, the first Malay-language newspaper in the world was born. It was 13 June 1869. The Colombo-based Jawi-script (called gundul by the Malays there) newspaper was described as revolutionary. The newspaper is integral to discussions on Malay writing in Sri Lanka.

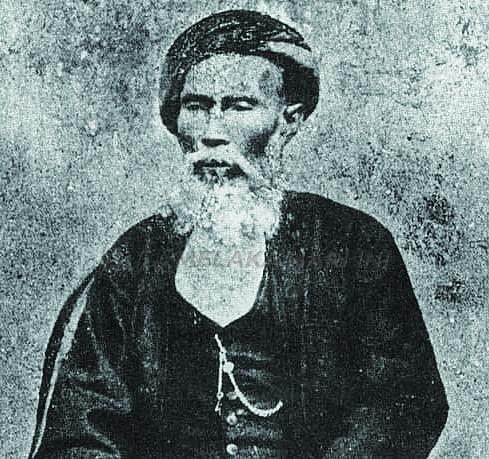

Alamat Langkapuri grew from the expressions of author, publisher, editor, and religious leader, Baba Ounus (Yunus) Saldin (1832 – 1906). Known as a progressive reformer, a custodian of Malay literary culture in Sri Lanka, he takes pride in Malay identity combined with strong Islamic elements. Baba Ounus was the grandson of Kapitan Pantasih, born in Sumenap, Madura in 1800. Kapitan Pantasih was brought into Sri Lanka as a recruit in the British colonial army. Baba Ounus, his grandson, was described as a fascinating pioneer in the shifting “frontiers of a Malay-Muslim presence on the stage of contemporary world events.”

Ceylon was historically and geography at the crossroads, between the Malay Archipelago (and the Malay Peninsular), and the Arab-Persian world. In her book Banishment and Belonging. Exile and Diaspora in Sarandib, Lanka and Ceylon, Rocit Ricci (2019) argues that the Prophet Adam’s imaginary presence in Sarandib/Ceylon potentially transformed the unfortunate accident of exile into the good fortune of returning “home” to Sarandib, at least in the imaginations of the descendants of those who had been banished there. She renders that no less formative for the Sri Lankan “Malay exilic imagination” was the Ramayana story. A key text popular in eighteenth-century Java as well as in diasporic Indian communities around the world, the Ramayana story is found in two incomplete Sri Lankan manuscripts of the Hikayat Seri Rama dating from the late nineteenth century.

What makes the Sri Lankan Malay-language versions of the Ramayana story a fascinating expression of “the intertwining of Ceylon’s exilic traditions and their place in the literary and religious imagination” is the fact that the exilic Adam and Sarandib Mountain are central to its telling of the story. It triggers the Malay imagination, in connecting to the name Alamat Langkapuri. A long pantun published in the July 11, 1869 issue of the paper; a wasilan, called the garisan Laksamana, for protection against approaching enemy soldiers on the battlefield, alluding to the magical line Laksmana draws around Sita to protect her when he rushes off to find Rama who has been tricked into chasing a demon ally of Rawana.

Ricci sees a connection between Adam and Sita, both of whose names refer to the “earth,” as “paradigmatic exiles.” In the Hikayat Seri Rama, Sita, even after her return from captivity in Rawana’s Langkapuri, continued as a form of exile, which Ricci suggests as a condition of “no possibility of a true, complete, unblemished return.”

Alamat Langkapuri, summarily expresses a variety of texts produced by the Malays in Ceylon – in the form of literary manuscripts, family diaries, genealogies and notes, and letters. It symbolizes cultural fortunes in the collective memory – the sarandib of exile. It presents the life of Sri Lankan Malay members of the British colonial Ceylon Rifle Regiment (or Malay Regiment, formed in 1795 and disbanded in 1873) and their descendants into full view.

Alamat Langkapuri was a depository of ideas and attitudes, of travel and mobility, of cultural contact and distance. It opens a jendela (window) to debates within the Malay community. The exiles were both shaped and guided by the Alamat Langkapuri. They in turn resonate through reflections and debates, contested between its pages. Alamat Langkapuri enabled the Sri Lankan Malays to develop relationships with their kins in the Malay Archipelago. The period saw the dawn of a new flow and exchange of information through the newspaper which became endemic in various parts of Asia beginning about the second half of the 19th century.

In her definitive book Ricci discusses the significance of Alamat Langkapuri, where alamat means ‘sign,’ ‘signal,’ ‘indication of things to come’ and, most pertinently, ‘new.’ The fortnightly in Malay has made it accessible, at least theoretically, to a broad readership beyond Ceylon’s borders in British Malay and Dutch East Indies.

Alamat Langkpuri functioned to disseminate international as well as local news, promoting the pantun and other verse forms, experimenting with advertising techniques, and inviting its readership to connect with each other and the broader communities by way of letters. Another significant feature is an early version of editorial opinions, the first in a Malay-language newspaper. Ricci notably argues that despite the keen interest in the Malay community’s religious affairs expressed throughout its pages, we well as the consistent reporting on matters having to do with British rule of the island, “neither the name Sarandib – echoing with Islamic tradition and identity – nor the name Ceylon with its contemporary relevance was selected for the newspaper’s title. Rather, it was Langkapuri. That choice, and the excerpt of a letter published in the newspaper, testify to the ongoing relevance of Ramayana imagery among the Malays.

The choice in the name Langkapuri could have to do the an awareness in the Dutch East Indies then, and of the existence of Sri Lanka and the threat of exile to there. She cites, what she terms as “the old Malay word disailankan, and its Javanese form diselongake [to be sent to Ceylon] as a verb used for ‘banishment.’ In Lombok, there is Gunung Selong (Mt. Selong), which is a corruption of the word ‘Ceylon.’ Hence the Wajah Selong [Views of Ceylon], which appeared later on 8 June 1895. Its readership was also beyond Ceylon. It was read in the Malay Archipelago as well.

This consciousness of Sarandib/Ceylon/Sri Lanka is also reflected in the name Gunung Srandil, near Cilacap on central Java’s southern coast. It bears the Javanese form of the name Sarandib. Nearby is Gunung Selok, which according to Ricci, may well be a misrepresentation of Selong. This is also a site of Javanese ascetic practice associated with foundational figures of the Mataram lineage, many of whose members were exiled to Sri Lanka. These are narratives, evoking a geography from India’s Coromandel Coast, to a string of islands linking Sri Lanka, stretching to the islands of Sumatra, Java and further east.

And these come in many forms – the dance, stone reliefs and inscriptions, and the wayang kulit. opening a window to the memory of exile and belonging. It arguably allows for an expansion of our definitions of the ‘Malay World’, and the inter-connectedness over time or Asian Muslim societies. From the middle of the seventeenth century, literary culture flourished, with striking similarities to the ones produced in the Malay ‘heartlands.’ The babad (chronicles), hikayat (prose stories), pantun (four-line poems) and syair (traditional verse) resonate homeland of in Alamat Langkapuri.

Langgani saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.