Asmara, Nun, Kenchana: Impressions of Early Malay Newspapers and Periodicals

THE dynamism of early Bahasa Melayu newspapers and periodicals have largely been ignored. In the universities, these are blatantly understudied. Students of journalism, of media, and of Malaysian history are uninformed, even on the names of the periodicals.

These are not deemed “newsworthy”. Malaysian journalism schools are ambivalent on Malaysian journalism history, or the history of Malay journalism. It is not only the fading of Bahasa Melayu journalism in Malaysia. It is also of the existence of a past, cosmopolitan and vibrant.

And now, there is no love for Bahasa Melayu journalism. Little known Jawi monthy Asmara (Love) appeared after the War in Singapura in 1955. It survived until 1958. Published by the Geliga (Genius) Publications Bureau, it was distributed by the Malayan Magazine Distributors, Singapore. They also distributed Rumaja (Teenager), and Irama (Rhythm). Kritik (Critic), Pedoman (Guidelines), and Pati (Extracts) published by Pedoman Press.

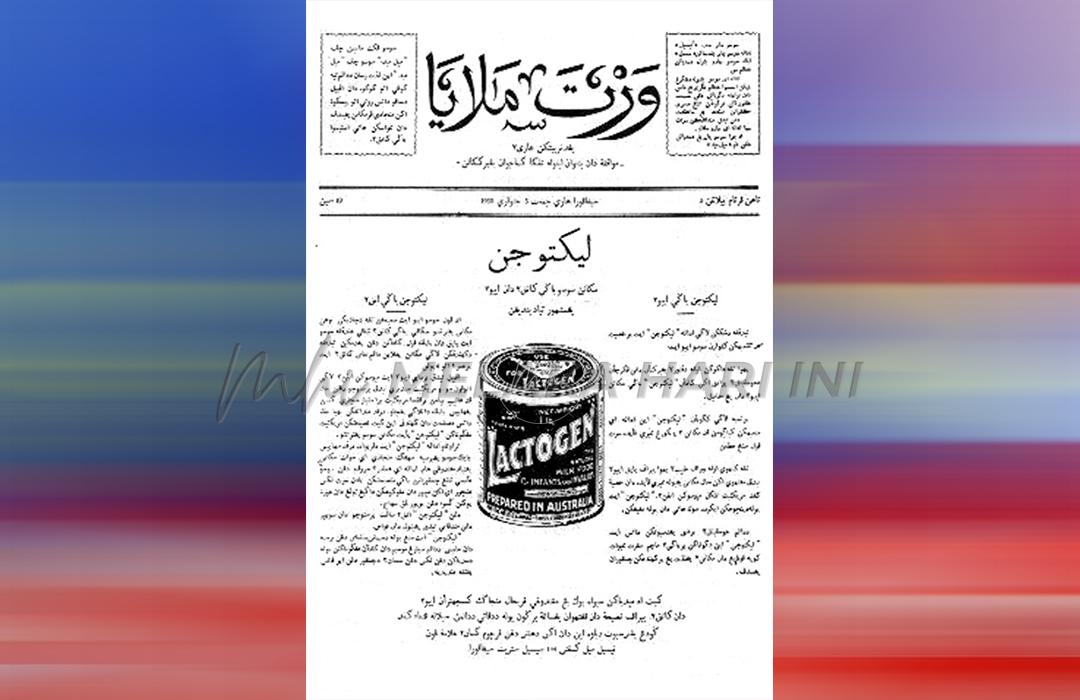

Before World War II, Pulau Pinang and Singapura would generally be associated with Malay printing and publishing, apart from places like Taiping, Ipoh and later Kuala Lumpur. Some are familiar with Jawi Peranakan (1876-1896), al-Imam (1906-1908) and the influential 1930s press in Warta Malaya (1930-1941) and Majlis (1939-1941). The latter two were once led by luminaries in the like of Onn Jaafar, Ibrahim Haji Ya’akub and Abdul Rahim Kajai.

Cosmopolitan Kota Bharu and Pasir Putih in Kelantan also published Malay periodicals from the more than a century-old Pengasoh (The Nurturer/from 1918), Kenchana (Gold or Golden/1930-31) to Terok/Tarok (1927). Terok, as listed in Roff (1961 and 1972) was published as an organ of the “Persekutuan New Club” in Pasir Putih. The founder of the club and of the monthly was Tengku Ismail Pekerma Tengku Pekerma Raja, the District Officer. Terok/Tarok could probably mean tunas, bud or sprout.

There was a fortnightly titled Nun published in 1926, up north in Yan, Kedah (listed as Yen). Edited by Haji Mohd. Said, the first issue appeared on 23 February and the last was in November of 1932. The title Nun, is the twenty-ninth letter of the Jawi alphabet, which prefaces the Surah Al-Qalam (The Pen) of the Quran. According to Muhammad Dato’ Muda in Tarikh Surat Khabar (Bukit Mertajam 1940), the choice of the name was held by some to have “mystic significance”. The first issue on 1 Rejab 1344 (25 December 1925, though 1 Rejab was 15 January 1926) may have been a sample issue. After publishing for two months, the journal expired, only to reappear on 2 September 1932 for “a further two or three issues.”

Names of early Malay newspapers and periodicals were in themselves reflective of the psyche and consciousness of its founders and editors. The titles like Neraca (The Scales/Singapura 1912-1915), Chahaya Islam (The Light of Islam/Singapura/1937), Al-Ikhwan (Brotherhood/Pulau Pinang, 1926), and Pedoman Islam (Guidelines to Islam/Seberang Perai, 1935); the Kaum Muda expressions in Idaran Zaman (Cycle of Time/Pulau Pinang, 1925-1930) and Saudara (Brother or Brethren/Pulau Pinang,1928-1941) and those expressing the sentiments of Kaum Tua in Lidah Benar (True Tongue) published in Klang and Suara Benar (True Voice) in Melaka.

Lidah Benar appeared weekly from 3 September 1929, edited by Mohd. Ali Ahmad al-Johari and Mohd. Damih Ibrahim. The other Suara Benar was the only newspaper (twice-weekly) published in Melaka before the War. Edited by Haji Mohd. Taib Haji Mohd. Hashim, Lidah Benar lasted for a few months from 2 September 1932 to February the year after.

The mantra of perjuangan (struggle) and kemajuan (progress) were endemic before the War. The semangat permodenan (modernizing spirit) in the names of newspapers and periodicals can be seen in in Mohd Eunos Abdullah’s Utusan Melayu (Malay Messenger/1907 – 21). It was the Malay edition, and much more than a translation of the Singapore Free Press. Other periodicals were Panduan Guru (Guidelines for Teachers/(Pulau Pinang, July 1922 – April 1945), Dunia Melayu (Malay World/Pulau Pinang/December 1928 to July 1930), Perkhabaran Dunia (World News or Bulletin/Singapura, February – March 1932), and Kemajuan Melayu (Malay Progress/Singapura, April – August 1932).

The periodicals provided news of events and prevailing ideas and trends. In 1935 Majallah Guru (Teachers Magazine) broadcasted on the idea of kemajuan (progress) in Malay society:

Urban Malays are progressive in walking round the billiard table; they have become expert actors in local operas; they can dance and sing well. They look smart in their suits (with collars for neckties) and various types of hats to match. They smoke cigarettes and opium (with pipes and stylets) and they are adept at gambling with cards. Is that what we call progress?

(Orang-orang Melayu ahli bandar maju benar mengelilingi meja biliad – di medan permainan – bijak menjadi anak wayang bangsawan – pandai-pandai tari menari dan nyanyi menyanyi, kacak benar memakai kot dan pentalon dengan kolar nektai dan topi bermacham – menghisap dapor atau puntong berasap dalam perkumpulan kalau di- hendap kelihatan kertas bersemarak dalam sahabat empat kaum shaitan, jadi-nya ada-kah betul bagitu yang di-katakan kemajuan itu)

The monthly was first published in Seremban in 1924, and subsequently in Kuala Lumpur and Pulau Pinang. It ceased publication in 1941. Khoo Kay Kim (1984) in Malay Papers and Periodicals as Historical Sources reminded that historians who wrote on change in Malay society, may not necessarily agree with the value of judgement passed by contemporary observers.

The attitudes of Malay periodicals toward the position of women was of much significance as an indicator of social consciousness and the idea of ‘progress’. In the early 1930s, there were two periodicals portraying women. One was Kota Bahru-based Kenchana (from April 1930), and the other Bulan Melayu (Malay Month) in Johor Bahru in June of the same year. While Kenchana was edited by Asaad Shukri Haji Muda, Bulan Melayu’s editor was a woman, Hajah Zin Sulaiman, better known as Ibu Zain.

Kenchana carried contents such as “Women’s Section”, “Kelantan Women’s Attire”, “American Women”, English Women,” French Women” and “Italian Women.” Bulan Melayu encouraged Malay women to look to the East, emulating the family and economic roles of their Japanese counterparts.

Langgani saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.