Malay Editorial Cartoons: Humour, Sarcasm and Self-Criticism

My earliest memory of editorial cartoons was Lat’s from the 1970s. These became more visible especially in the 1980s and 1990s through the New Straits Times. And there was the syndicated Senyum Kambing in Utusan Malaysia during the same period. Editorial cartoons comment on the issues of the day, somewhat an overstatement of the spirit of the times.

The medium of the cartoon first appeared in the Malay-language newspapers in the 1936. It was the first issues of the weekly pictorial Warta Jenaka, dated 7 September 1936. The use of cartoons in newspapers seems to have been a direct borrowing and adaptation from European, more specifically British cartooning, as disclosed by scholar and cartoonist Muliyadi Mahamood in The History of Malay Editorial Cartoons [1930s-1993] (2004). The book provides a comprehensive survey of the the cartoon narrative in the Malay journalistic landscape. Another, a popular appraisal of cartoons in early Malay periodicals is Senda Sindir Sengat by Zakiah Hanum (1989).

While working on a project on Malay views of the West a decade ago which led to the 2019 publication titled as Revisiting Atas Angin: A Review of the Malay Imagination of Rum, Ferringhi and the Penjajah, I discovered another side to the discourse through editorial cartoons. This centres on Malay identity through the portrayal of the Other – the Arabs, Indians, Chinese, other non-Europeans, as well as Europeans. The Arabs and Arab Peranakans were identified as foreigners in disguise. In the cartoons, the Chinese and Indians were described as ‘orang dagang.’ The narrative of grievance dominated – marginalized in their Tanah Air. This was represented through the caricature in Warta Jenaka.

Malay cartoons first appeared during the period through the works of several regular and freelance cartoonist in three major newspapers, namely Warta Jenaka, Warta Ahad and Utusan Zaman. In the interwar years. The Malays in Malaya were aware of the various conflicts in Europe, the Arab world, China and Japan. Malay periodicals and newspapers at that time provided the vehicle for expression and nationalist sentiments. Cartoons and caricatures began to emerge as satirical and political manifestations evoking the Malay consciousness.

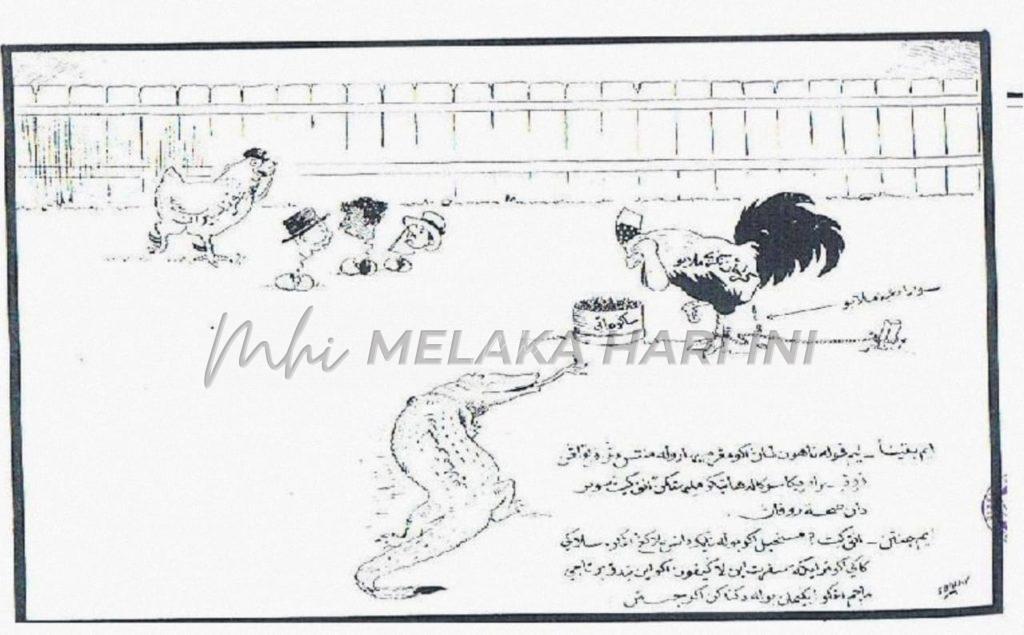

Ayam Jantan (Kerajaan Negeri Melayu): “Anak kita? Mustahil aku boleh naik di atas belakang engkau, selagi kakiku trikat seperti ini. Lagipun aku ini tidak bertaji macam engkau! Bagaimana boleh dikatakan aku jantan.”

Makanan ayam = Sagu hati

Tahi ayam = Suara orang Melayu

Biawak = Orang Besar Melayu

(Trans.

The Hen [Administration]: “For fifty years I have been sitting on my eggs, and now they have hatched thanks to the Amerian Professor’s help. I am so happy to see how healthy and strong ‘our children are.’The Rooster (Malay government): “Our children? How could I have climbed onto your back, with my feet tied like this? Besides, I don’t have spurs like yours! How can I be called a male?”

The Rooster’s Food = Consolation

The Roosters Excrement = the voice of the Malays

Monitor Lizard = Malay aristocrats and administrators)

Caricature by S. B. Ally, Warta Jenaka, 20 January 1938, p. 10

The other person behind the cartoons was journalist and editor Abdul Rahim Kajai. He saw the Europeans and British in Malaya as ‘bangsa pemerintah’ (ruling race) who dominated the administration, the economy and education. They told the Malays to stand firm amid the growing stream of ‘orang dagang.’

Abdul Rahim Kajai’s alter ego was Wak Ketok (Uncle Knock). The relevance of Wak Ketok lies in the identity of the Malay and the notion of the Other. The Malay was increasingly being defined against both a ‘Chinese’ and a ‘Malay-Arab’ or a ‘Malay-Indian Muslim’ racial Other. Wak Ketok first appeared in Utusan Zaman – the companion Sunday paper for Utusan Melayu – on 5 November 1939.

Wak Ketok was the voice Kajai, through the form given by cartoonist Mohd. Ali Sanat, who contributed to the illustrations. Wak Ketok was a “window” through which we view the engagement of the Malays to colonialism and their Muslim Other. Wak Ketok was engaged in a discourse about the ‘bangsa.’

Interestingly, the Minangkabau Rahim’s alter ego in Wak Ketok was a Javanese character. Wak Ketok came to embody Kajai’s personality and thinking. Wak Ketok was critical of the pretensions of the wealthy Malay/Arab community – their Westernized lifestyle, their assumed piety while at the same time being depicted as engaging in drinking and gambling, which Islam forbids.

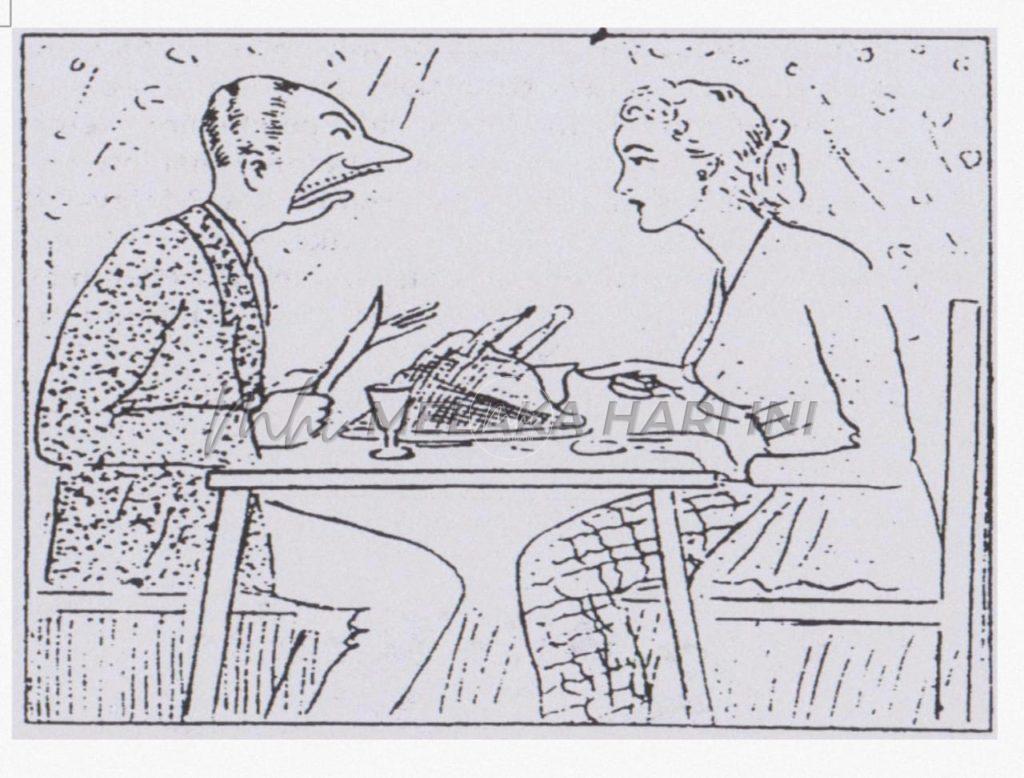

A prominent feature of the Wak Ketok cartoon itself is the nose. His nose seems at times much longer and more pronounced (when shown in profile) – especially when he is in the guise of an Arab or a Western (-ised). Among the Malays, Europeans (and Westerners) are commonly seen as possessing sharp, pointed noses (hidung mancung). The foreigner, in Malay cartoons through the ages, have pronounced noses of the mancung type. While Kajai (through Wak Ketok) was critical of the Arabs for their moral shortcomings, their extravagant lifestyles, their presuming to lead the Malay-Muslim community, he was equally critical of Malays for their deference to the Sayyids for their lack of self-pride and support of fellow Malays.

The anti-Arab sentiment was presented in several ways by Wak Ketok. Sometimes fused with the image of the West, one cartoon showed Wak Ketok having a Western-style dinner with his wife – fine dining. The image displayed the use of cutlery, which was alien to the common Malay. Acting as an arrogant Arab Peranakan, the sharp-nosed Wak Ketok was portrayed in a suit. The Arab Peranakan at that time were seen to be the purveyors of modernity, and obsessed with the West.

(Trans.Where did Wak Ketok Get His honourable Title?)

Utusan Zaman, 20 July 1940, p. 17.

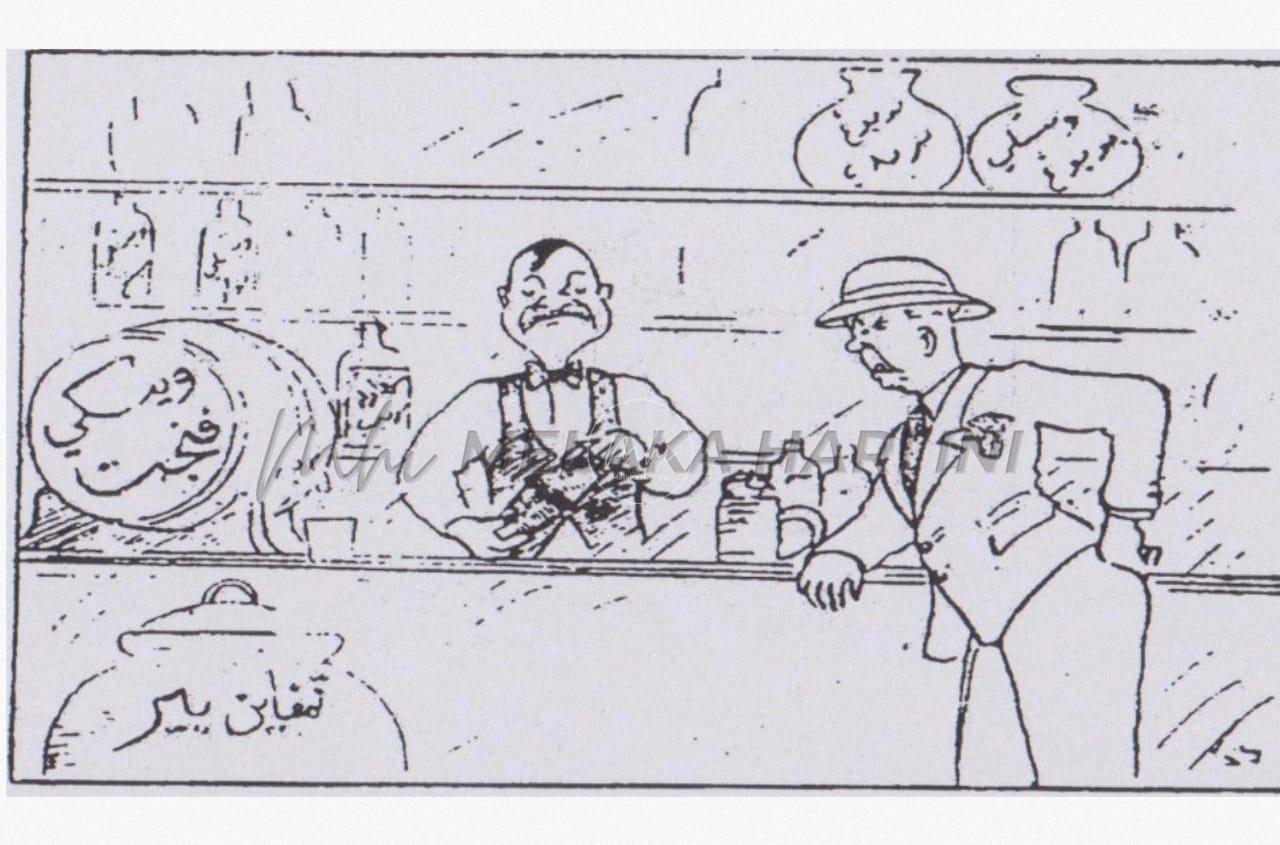

Another showed Wak Ketok preparing a cocktail for an Arab Peranakan who was waiting. In most of Wak Ketok’s caricatures, the Arabs were seen as pretenders and hypocrites. Their image mediating between the Malay and the European.

Langgani saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.