Resting Place of an Idea: The Power of Sunan Kalijaga

The blurb at the back cover of the paperback describes Java’s pilgrimage culture as a dense, batik-like pattern of contradictions: seriousness collides with laughter; curiosity with bewilderment; piety with scepticism; intense spirituality with, in some places, the joy of shopping.

In Java’s “inner archipelago,” as the author describes it, Islam is fused with local history. It evokes the interplay of the power of place and a pastiche of devotional practices with roots deep before the Islamic past. Indonesianist George Quinn in his book Bandit Saints of Java (2019) themed each chapter around a particular saint or pilgrimage site. In this essay I draw upon the theme from Chapter One. Titled “Drawing a line to Mecca: Sunan Kalijaga and the contest for authority in Javanese Islam,” Quinn, a speaker of Indonesian and Javanese, delves on Java’s most beloved saint.

More than 500 years ago, a cohort of religious teachers known as the Wali Songo – the Nine Saints – decided to build a mosque in Demak, on the north coast of central Java. According to popular tradition, the mosque was built in one night. It was narrated that four of the nine saints (wali) were given a job of finding trunks of wood to make a quartet of pillars that would support the building’s high, pyramid-shaped roof. Three of them – Sunan Gunung Jati, Sunan Bonang and Sunan Ampel – each located a massive tree, cut it down and dragged it into Demak. But the fourth, Sunan Kalijaga, had been away meditating on the distant south coast and turned up late.

As Quinn tells us, “he didn’t have time to go hunting for a tree, so on the night of construction he contributed a pillar made from off-cuts of timber that littered the construction site. He glued them together and bound them with cords and iron hoops. It was just as strong as the other three pillars.”

What we see today is that each of the four central pillars is labelled with the name of the wali responsible for it. In between prayer times, visitors would slip into the airy ambience of the mosque and walk from pillar to pillar touching each of them. Invariably, they linger reverently at Sunan Kalijaga’s saka tatal (the pillar contributed by him); and from time to time flower offerings are placed at the foot of the pillar, “much to the annoyance of mosque officials.”

The Grand Mosque in Demak, one of the oldest in Java, built sometime in the 1470s, is to many Javanese “a model representing the house of Islam,” notes New Zealand-born Quinn, an erudite observer of Indonesian life. The famous pillar is seen as a miracle sent down the ages by Sunan Kalijaga to enlighten the present, the pillar symbolizing collective solidarity and authority. For a few, the pillar is also an icon of modern nationalism, mirroring the official motto of Indonesia, Bhinneka Tunggal Ika – “In diversity there is unity.” It gives expression and spiritual essence to the island nation’s aspirations.

Most of us are familiar with the “team photo” of the Wali Songo. They were said to be among the earliest teachers of Islam in Java in the 1400s and 1500s. Their tombs dot the knobbly line of the north coast of Java, from Cirebon on the border between Central Java and West Java, to Surabaya in the East. We do not know how the nine saints looked like. It is also unlikely that they ever met as a group. Quinn argues that even their exact number and details of their lives are indistinct in the haze of distant history and “some even doubt they existed at all.” Such claims are unsettling for many Javanese.

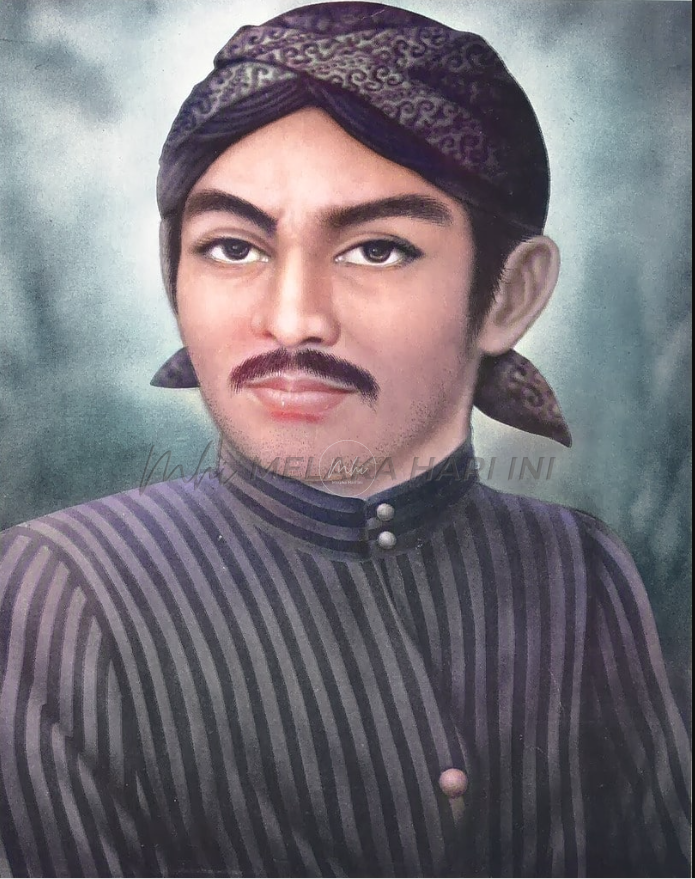

It is exactly for this reason that what Quinn calls “the team photo” is interesting. It is not historical but rather a modern imagination of sainthood projected on to the evidence-bereft screen of the past. All the saints are beturbaned, except for Sunan Kalijaga – in the front centre. All looked like puppets in the cast of a shadow play, with eyes “stare with placid, unflappable conviction.” Quinn describes them as radiating authority without being threatening or overbearing.

The Wali Songo moniker was said to be derived from the plea by Sheikh Jumadil Kubro to Ottoman ruler Sultan Mehmet the first. The Sheikh came to Java from Turkey sometime in the 1400s. The sultan agreed and “nine learned ulama – each with his own portfolio of specialist expertise – would be appointed to teach Islam in Java.”

From the Nine Saints, Sunan Kalijaga was different. While the other looked Arab, clad in turban and robes, Sunan Kalijaga wears a blangkon (close-fitting batik headcloth), a beskap or sorjan (mandarin-collared jacket), and a long batik sarong. The styles of “traditional” men’s dress probably developed in the nineteenth century. That would be some 300 years after Sunan Kalijaga lived.

Sunan Kalijaga was earlier embodied as Brandhal Lokajaya where brandhal means “gangster” or “bandit.” It was told that he encountered his opponent, the wali Sunan Bonang, “who was wielding the staff of Islam.” Sunan Bonang saw and noticed that Lokajaya was no bandit but a fellow saint ignorant of his sainthood. Upon handing his staff to Sunan Kalijaga, Sunan Bonang left. After a year, Sunan Bonang returned and instructed Sunan Kalijaga to head west to Cirebon and there meditate on a riverbank for another year. The name given to him by Sunan Bonang was Sheikh Malaya.

In Ceribon, Sheikh Malaya established a riverside religious school. Every night after prayers, Sheikh Malaya would go to the riverbank and meditate. It was said that to ward off the beguiling but dangerous forgetfulness of sleep, he would slip into the river and meditate for hours immersed to his neck in the cool current, drifting away in meditation. The Javanese call this practice as tapa ngeli. Sunan Bonang again visited Sheikh Malaya after one year. Impressed with his commitment, he ordained him a saint by bestowing a new name – Sunan Kalijaga – “the saint who kept a vigil at the river.”

According to Quinn, a sprawling metropolis of stories sprung around his exploits as a wandering teacher. The story architecture is distinctly Javanese. Among Sunan Kalijaga’s accomplishments was his exploits in wayang kulit (shadow play). He was a puppeteer, a master of that most of Javanese arts. He was said to have brilliantly shown audiences the Islamic reality behind ancient Hindu stories, with its characters, intricate iconography, symbolism, and philosophy remaining Javanese in identity.

For many Javanese, Sunan Kalijaga’s life story is the embodiment of Islam in the Javanese “inner archipelago.” For others, it is an allegory. His tomb, about two kilometres away from Demak’s grand mosque continuously receives tides of visitors.

#####

Next week:

Ship and Sha’ir: Hamzah Fansuri’s House and Heart

Langgani saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.