Stories from the Verandas: Another History of the Tanah Air in The Genealogy of Kings

When The Genealogy of Kings: Sulalat al-Salatin by Tun Seri Lanang was released by Penguin (Penguin Random House SEA) in 2020, I would imagine it would create a new aesthetics and imagination on Malay history and society. Often erroneously translated as the Malay Annals, the narrative is central to the history of the Malay Archipelago. Translated by Sasterawan Negara Professor Emeritus Muhammad Haji Salleh, the hikayat was written on behest of the Raja di Hilir, literally, Lord of the Upper Reaches.

The Raja di Hilir had requested the Vizier (bendahara/high ranking official/minister) “to inscribe for us a genealogy of all the Malay kings and their customs, together with all the ceremonies of the palace, so that they may be made known and observed by all our descendants who come after us and from them derive some benefit.”

I was first engaged in the world of the Malay hikayat through Sejarah Melayu at Penang Free School in the mid 1970s. It was taught as a piece of literature of incredible tales. We consumed it as moderns, segregating fact from fiction, perhaps too fictionalizing what was factual. We regarded it as myth and imagination within the spatiotemporal world of the Malays; subconsciously confining the identity to the Malay Peninsular. In a way, the Sejarah Melayu is generally seen as providing us with the geography of the divine and the miraculous, of a time before reason, rationality, and the invention of factuality.

In its widest meaning, the Sejarah Melayu is ‘literary.’ Muhammad Haji Salleh in his introduction makes a pertinent remark in how the Malays conceive of what we understand as history. History was not measured through written notes and documents. Instead, the sophisticated instruments of oral expression and its musical qualities are celebrated, he explains. Since time immemorial, the leitmotif of orality and aurality dominates the Malay narrative of the past; and with social media, we see this in the present. Modern documents, so called ‘empirical facts’ are only important only as part of the narration of happenings and their interpretations. Truth, therefore according to Muhammad “may not only be sought in the written pages, but also in the words spoken by the bards and singers.”

The Genealogy of Kings challenges the Rankean notion of history, that the writing of the past be based on empirical evidence. The Rankean school rejects the moral and ideological contexts. It collapses the relativism in Sejarah Melayu where (historical) time is measured against the wide flow of events of birth, death, reigns and abdications of the various rulers. These were used as time markers. We can only estimate the years and the decades from our location in modernity.

But we can be certain that the Sejarah Melayu was read by the rulers of the many kingdoms in the Malay Archipelago for some centuries, and transmitted orally to the larger part of Malay society. Before the printing press, print, mass production and reproduction, the Malay Archipelago was the world of the hikayat. The Sejarah Melayu, and what we moderns conceive of literature and all its forms, which includes the mantera (incantations), pantuns, gurindams and syair (proverbs, poems, verse narratives) were consumed in ways not much different in our use of new media technologies and the social media.

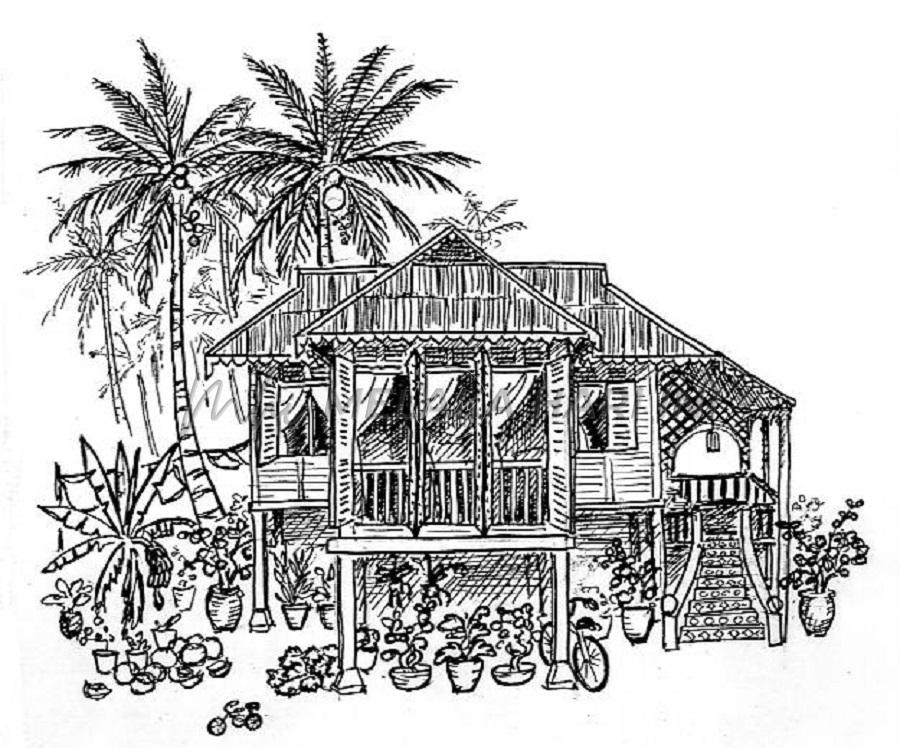

If the geography of the divine pervades then, now it is the virtual, creating many roads to the past. Then, there was only one past, and that past was ‘instructive’, didactic. The Sejarah Melayu is still that definitive past, as integral to that pool of knowledge and wisdom of the penglipurlara (storytellers, bards). The oral performances, most popular and entertaining, were a source of teaching, and easily available like the touch on the screen. The stories reflected the range of experience of the Malays themselves. Muhammad refers to the availability (and accessibility) of the stories in that they “were told on the verandas, and in the out rooms of village houses, under the trees of the yard.” The stories were told to the children to whom these “later became the reference points in their lives.”

If history was written for the benefit of the audience, then clearly the Sejarah Melayu was arranged to be a didactic collection of episodes. The hikayat sets out to teach by example and commentary, directly or tangentially. We see this in the unjust King of Singapura, who sentenced to death his wife a senior minister’s daughters after accusing her of adultery, without due investigation. As an act of rebellion, the minister opened the gates of the city to his Javanese enemies, resulting in its sacking, and his exile. Another example given can be seen in the last episodes of Sejarah Melayu, which parallel those of Singapura, where favouritism, negligence and injustice brought about divisions among the Melakans – and as they say, the rest is history.

The Sejarah Melayu or The Genealogy of Kings is perennial in its relevance. It speaks to the Malay collective – the different phases, successes, crisis and failures. The themes resonate present realities and identities. The hikayat evokes ideals and philosophy of government and governance, responsibilities and rights of rulers and subjects. It is the ever-present past. The Sejarah Melayu brings the personae of the Tanah Air. The embeddedness of budi enables us to narrate truth, define justice, and embody adab.

Langgani saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.