Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa: The Genesis of Kedah’s Global Consciousness

A re-reading of Rum/Rom as narrated by such texts as the Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa (HMM) is inevitable. This is to demythologise the expanse of the Malay world view and imagination. The Raja Rum, whether understood to be a Greek, Persian, or Turkish, is a popular figure in traditional Malay literature. An array of the kings of Rum/Rom occurs in many Malay literary genres. From the known (or unknown) writers, we know much of Malay society, encounters with and influences from the outside world, as the Malay would say dari dunia luar.

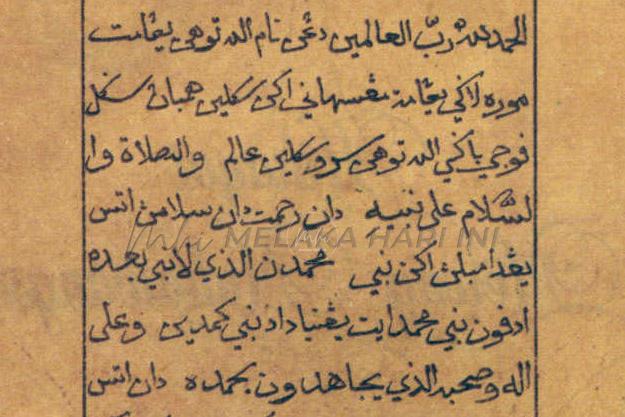

Still, little is known about the Hikayat. Scholar of Malay, Hendrik J.M. Maier (1988), in his study of the Hikayat discussed how its compilation, value, stories, and prestige have been unjustly questioned, ignored or ridiculed by most 19th and 20th century students and scholars, many of whom were produced by the modern educational systems.

Maier attributed this attitude to the popularity of the English translation of the Sejarah Melayu. Thus the Hikayat had the disadvantage of being “read against the background of the Sejarah Melayu, and ever since, this primacy of the Malay Annals has never been subverted.”

Despite this disadvantage, Maier significantly argued that the Hikayat could be seen as a fine manifestation of 19th century culture, dominated by oral-aurality. It drew upon fragments of a shared knowledge into a narrative. The Hikayat could also be used as a fine illustration of the discontinuities that emerged in the field of Malay knowledge coincident with the introduction of Western-oriented education and printing techniques. This eventually resulted with a break with the past.

The uneasiness among recent and earlier Malay scholars and intellectuals about the validity of the Hikayat heritage has been quite evident. This was noted by history and Asian Studies scholar Maziar Mozaferi Falarti (2014). He lamented that as a historic source, the Hikayat has been unjustly questioned as to its reliablity. Much of what is have been conceived as fiction, myth and fantasy. Nevertheless, Falarti, as seen through his book Malay Kingship in Kedah: Religion, Trade and Society, is one of the earliest modern scholars to have used a Malay classical work, in this case the Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa, as a textual foundation for the spiritual legitimacy of a Malay kingdom, and subsequently its history and society. Many have ignored these key aspects of the Hikayat as a source in understanding the domain and the Sultanate of Kedah.

Stories in classical Malay texts, such as in the Hikayat can shed light to the extent of indigenous or foreign influence that have impacted Malay society and systems of government in the pre and post-Islamic periods. According to Falarti, the Hikayat closely follow and resemble those of Persian (particularly Shahnameh or Book of Kings and the Safavid era’s (1501/02-1722) Hekayateh Simurgh (or Gheseyeh Soleyman va Simurgh), and South Asian (Ramayana and Jataka) stories. These inclusions were astounding and have never been properly examined. There are also references to other Southeast Asian sources or traditions. Examples are the Naga worship and wayang kulit.

Falarti argued that the Hikayat indicated an attempt by its authors to construct a text and a theme that would appeal to a wider audience without compromising Kedah’s unique foundation narrative and royal genealogy. The mode of conversion of the Kedah ruler and peoples to Islam as suggested by the Hikayat, is a powerful testament to the way the monarchy and political infrastructure viewed the historic event from within, or alternatively wished to be viewed by the indigenous population and foreign visitors.

In the beginning of the Hikayat, the authors clearly stated that it is the continuation of the Rama story (referring to Ramayana but without mentioning it by name): “After the war of Sri Rama and Raja Hanuman, the island of Langka was deserted except by the bird Geruda”. Falarti believed this referred to the island of Langkawi – the Ramayana island of Lanka, Langka or Langkapuri. As such, the Hikayat must be considered as a relevant and serious source for the study of Malay and Southeast Asian history, and be viewed as a repository for a combination of sources.

It can be further argued that the key aspects of the Hikayat comprising foreign elements, pre-Islamic, as well as popular characters and indigenous stories from the wayang kulit or oral traditions, only indicate the popularity of such stories and traditions amongst the general population and at the court. It may also point to its numerous authors and compilers. We see these plausible in the presence of Persian, Indian, Chinese and Thai elements in the text.

The inclusions may not only refer to the knowledge of such stories and traditions by the Malay or foreign author/s or copyist/s at Kedah but also their elegant integration into the indigenous context and world view. Falarti in particular cited the integration of stories traditionally associated with Iran. Such from the Shahnameh and Hekayateh Simurgh are unprecedented in the Malay world. The Hikayat’s “inclusion of the story of Garuda, Prophet Solomon and the marriage of a prince and princess, from the east and the west, in fact run parallel to the little known Persian story of Hekayateh Simurgh. Simurgh is the Persian equivalent of Garuda and a mystical bird.”

The Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa is not history. It provides us with another source in answering complex questions about ourselves and our society; and significantly manifests shared pasts and memories. The Hikayat connects and transcends civilizations. Demystifying Rum/Rom (Rome) in Malay consciousness is a good reason for its reintroduction beyond the 2011 film.

Langgani saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.