Unveiling Tempo: A Cultural History

INDONESIA’S Tempo magazine provided a window to the nation’s New Order. The weekly was popular among some of us in Malaysia journalism schoosl back in the late 1970s. In June of 1994, Tempo was banned together with several other Jakarta-based periodicals

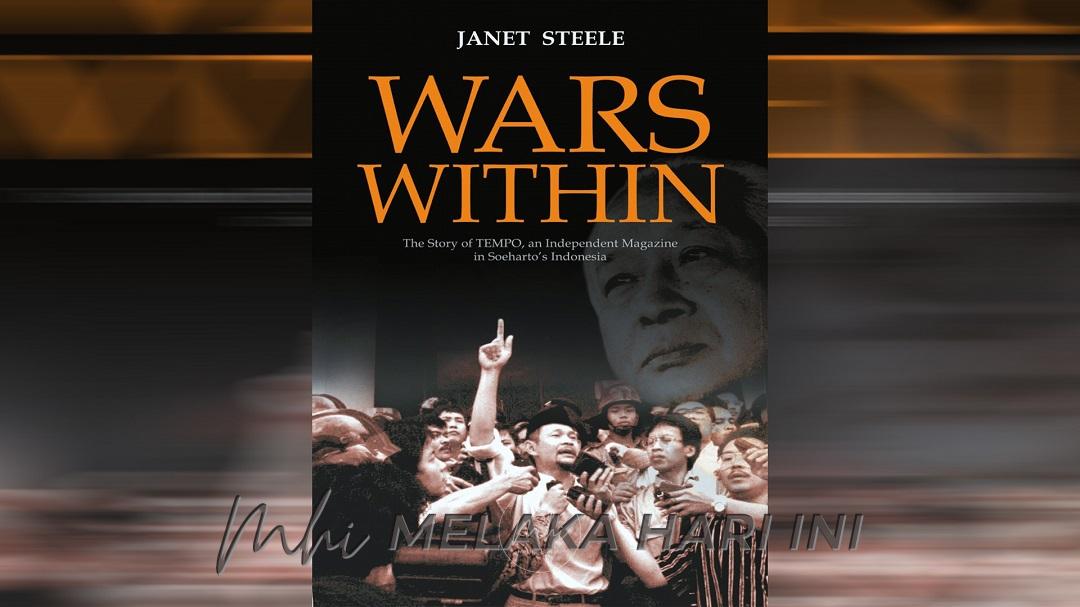

Editor Goenawan Mohamad’s words “Why should the army fear us when they are the ones with the guns,” scribbled in the paper napkin was kept for a long time by the author of Wars Within: The Story of Tempo, an Independent Magazine in Soeharto’s Indonesia (2005). Janet Steele, journalism academic from George Washington University, and a frequent visitor to Indonesia, was intrigued with the media in Indonesia. In Jakarta, she was connected to the many informal networks of ex-tempo employees.

Tempo was founded in 1971, at the beginning of the New Order – the term given to the era that General Soeharto brought to power in 1966, after a failed coup attempt ended President Soekarno’s experiment with Guided Democracy. The magazine’s founders were all members of the “Generation of ‘66’,” mainly students and activists, who, together with the military, brought an end to Soekarno’s rule.

Tempo, sometime called Indonesia’s version of Time magazine, had earlier supported certain aspects of the New Order. It aligned itself with the “technocratic” policies of Indonesia’s Berkeley-trained economists who emphasized rational planning and economic development that would be the hallmarks of the New Order.

Tempo had friends in the government, “and there were friends in Golkar.” Golkar was the political engine of the New Order – Soeharto’s organization of “functional groups.” It was Harmoko, the Minister of Information, who signed the letter that banned Tempo on 21 June, 1994. For those who may remember, Harmoko was one of the advocates for a New World Information and Communication Order in the 1970s, together with several others then coming from Non-Aligned Third World bloc. And this included Mustapha Masmoudi from Tunisia.

According to Steele, Tempo grew strong and wealthy while Soeharto’s economic development plan, bolstered by the rise in oil prices of the mid-1970s, transformed Indonesia into one of the new “Asian Tigers.” Its editor Goenawan Mohamad’s often-quoted statement that editing Tempo was like trying to pilot a hijacked plane with the journalists as his passengers, was a grim reminder of the perils of editing a magazine during the Soeharto years.

The magazine was temporarily banned in 1982. Scholar of Southeast Asia, Benedict Anderson, described Tempo as having the style of “mannered knowingness.” Steele saw Tempo as an independent institution, a truly “non-government” organization. This was because the much admired magazine, also from among the Malay intellectual and literary elites in Kuala Lumpur then, offered independent perspectives on the nation and society of Indonesia in ways that were subtle but unmistakable. It rankled with its enemies in Soeharto’s New Order.

But the banning of Tempo marked the beginning of the end of the New Order. The popular reaction was unprecedented. The biggest surprise “was the outburst of support from ordinary people, middle class Indonesians who had kept silent throughout the nearly thirty years of Soeharto’s rule,” observed Steele. The magazine’s readership was relatively small – weekly circulation was never higher than about 190,000.

Tempo was, to sociologist Arief Budiman, a kind of “space,” a place in which writers could exchange ideas with relative freedom. It was Indonesia’s only world-class magazine. It was argued that if Tempo’s enemies had expected the magazine to crash and burn as a result of the 1994 banning, they were mistaken. The banning had the unintended effect of freeing editor Goenawan Mohamad from his government “hijackers.”

With Tempo gone, Goenawan had nothing to save. Goenawan was completely free. His magazine did not exist. Steele had earlier planned to write about Tempo as “the magazine that doesn’t exist.” But that was no longer possible.

She realized that the weekly was much more than a very portent symbol of freedom of expression. For the twenty-three years prior to the banning, Tempo was Indonesia’s most important and the only weekly news magazine. It was an institution. It helped to shape and define modern Indonesia. The culture of Tempo had influenced on what was worth talking about.

Tempo occupied an ambiguous position. A product of the New Order, it presented independent points of view, often at considerable risks. It was like the epic battles of the Mahabhrata. Tempo’s struggles marked a war within the New Order. Steele called it fratricide, or perang saudara, a war of brothers. The civil war within was like the wayang kulit, nothing in black or white.

From the beginning, Tempo writers were told that their articles should read like “like stories.” In the early 1970s, Goenawan’s writers had been influenced by the work of Tom Wolfe and other “new journalists” from America who applied literary techniques to the practice of journalism – scene setting and character development. The New Journalism mood also prevailed among journalism students in Malaysia – at the Shah Alam and Minden campuses. In the early days, Tempo was run by artists and writers. It was not strictly deciding what’s news.

Goenawan and his team provided a new “language” to journalism in Indonesia. Its narrative meanders from one topic to another. Tempo was like reading a novel. The enterprise was somewhat responding to the global modernization project of the 1960s. Theorists like W.W. Rostow, Daniel Lerner and Samuel Huntington, the darling of the West in the development of the rest of the world.

Tempo also wrote against that scenario, the spectre of Communism, and the Cold War vision on the post colonial states in the Malay Archipelago. Goenawan and his Tempo were playing to the tune of Bob Dylan through their portent essays strategizing not only within a repressive press system, but talking back to hegemony and liberalism.

NEXT WEEK : The Hispanized Malay

Prof. Dato’ Dr. Ahmad Murad Merican is Professor of Social and Intellectual History with the International Institute of Islamic Tho ught and Civilization, International Islamic University (ISTACIIUM). He is a Senior Fellow with the Southeast Asia Research Centre and Hub at De La Salle University, Manila, the Philippines.

Langgani saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.