Utusan Melayu: The Radical Malay Newspaper

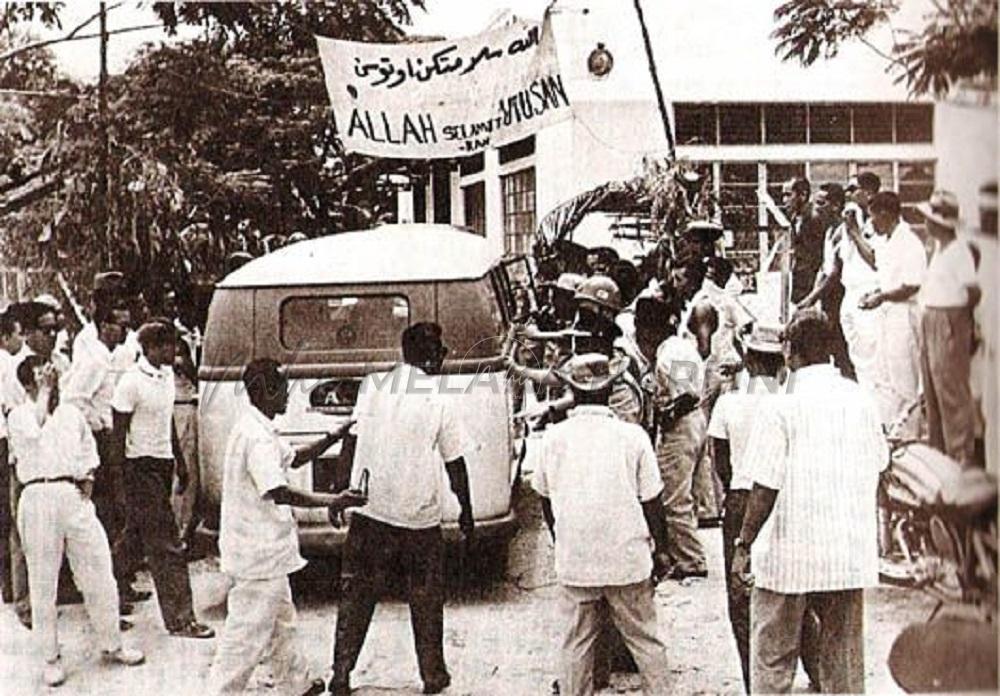

On 21 July 1961, Utusan Melayu’s editors, journalists, administrative, printing and other staff totalling some 115 people launched a strike in Kuala Lumpur protesting political intervention on the newspaper. Thirty others in Singapura also joined. The strike lasted for 93 days. They picketed for 24 hours a day opposite the Utusan Melayu office at Jalan Lima off Jalan Chan Sow Lin. Many lost their jobs, friends and comrades.

The newspaper Utusan Melayu had radical aims from the day Utusan Melayu Press Limited was established on 15 June 1938. In the early days of Malay journalism, the manner in which Utusan Melayu appeared was unlike other newspapers. Utusan Melayu has been narrated as the first Malay-owned, funded and managed newspaper in Malaysian journalism history. Although the first Bahasa Melayu newspaper in Malaysia appeared in 1876, Jawi Peranakkan, and many others were financed and led by the Jawi Peranakkan and the Hadhrami/Arab Peranakkan community mainly based in Singapura and Pulau Pinang.

In Malay journalism and newspaper history, the initial gathering of about 20 people at the house of Daud Mohamed Shah in Siglap, Singapura, was a little-known watershed event. The purpose of that meeting was to operate a daily newspaper through the offering of shares. Some $12,500 were raised by a total of 542 shareholders. With the funds, a number of used printing presses were purchased from England, and placed at No. 64, Queen Street. The person assigned the task was Yusof Ishak.

In April 1939, Ishak Muhammad (Pak Sako) and Zainal Abidin Alias (Zabha) left the Arab-owned Warta Malaya to join Utusan Melayu. Warta Malaya’s editor Abdul Rahim Kajai was to follow suit. One month later, the maiden issue of the newspaper appeared on the streets, with the slogan “Malay National Daily Newspaper.” It was sold for 10 cents.

The Utusan Melayu strike was an event resisting the intervention of political ideology in the organization. It was to prevent the taking over of the company and the newspaper by UMNO. The decision to organize the strike was when UMNO president, Tunku Abdul Rahman sent a member of its Supreme Council, Ibrahim Fikri to be the newspaper’s Managing Director cum Managing Editor. Ibrahim immediately transferred Utusan Melayu’s Editor Said Zahari to Singapura. He then decreed Utusan Melayu to support policies of the government.

Said protested in the name of maintaining independence and editorial integrity. He and his colleagues feared that Utusan Melayu would be the voice of UMNO. They refused to negotiate with Ibrahim. Instead they had asked to meet with the Chairman of the newspaper’s board of directors, Senator Hashim Awang, whom they thought would be sympathetic to their cause – that of an independent press. Their demands to meet the chairman was ignored.

The strike drew public attention. Names like Said Zahari, Usman Awang, Salleh Yusoff, Tajuddin Kahar, Zailani Sulaiman and Rosedin Yaacob were quite will known to the Malay-reading public at the time.

In his 2013 book, Di Depan Api, Di Belakang Duri: Kisah Sejarah Utusan Melayu, Zainuddin Maidin, Editor-in-Chief, popularly known as Zam, recalls that Said Zahari and his editors took the opportunity to steer the newspaper away from UMNO by taking a more open and aggressive stance toward Parti Rakyat, the Socialist Front, and supportive of Indonesia. And an uncompromising anti-UMNO position. Said had changed the weekly Mingguan Utusan Kanak-Kanak to the Mingguan Utusan Pemuda to promote the writings of the socialist and communist groups in Singapura.

Much earlier on, Tunku Abdul Rahman, even from before he became UMNO president, had already seen the potential of Utusan Melayu, and its importance to the Malays. The Tunku was also a regular contributor to the newspaper, using its pages to transmit his views and values. At the same time, UMNO strongman Hashim Awang, was the biggest shareholder of the newspaper. He had appointed UMNO members to the newspaper’s board. However, Yusof’s position as Managing Director was retained.

According to Zam, the Tunku, who wanted to ensure that Utusan was cleansed of subversive elements, had one day invited Yusof, together with the newspaper’s legal adviser Lee Kuan Yew for dinner. The event at the Tunku’s residence was also attended by Aziz Ishak (Yusof’s younger brother), who was then the Minister of Agriculture. It was a meeting to discuss the cooperation between Utusan Melayu and the government.

The meeting also raised the position of A Samad Ismail. Tunku later signalled Yusof to remove Samad as the newspaper’s Deputy Editor. The Tunku had smelled that Samad was “pro-communist or communist.” He informed this earlier to Lee Kuan Yew. In the course of preparing his book, Di Depan Api, Di Belakang Duri, Zam related to me that Yusof was caught in a dilemma.

Yusof could not easily remove his close friend and confidante for more than 20 years. They were the genesis of Utusan Melayu. Yusof did not remove Samad from Utusan, but instead transferred him to Jakarta as the newspaper’s correspondent. He was pressured to do so by the Tunku. Utusan Melayu was “owned” by Pak Samad and his family as much as by Yusof’s. He returned the same year and later became first editor of Berita Harian in Kuala Lumpur.

In the late 1980s, while teaching at a Journalism School in the Klang Valley, I invited Pak Samad as guest lecturer. Later I asked him on why he was transferred to Jakarta in 1957. His answer never came.

#####

Next week:

The Maria Hertogh Tragedy: Karim Ghani’s ‘moving spirit’

Langgani saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.